‘What Else Would You Name Her?’: A breast cancer patient, a pregnancy, and a doctor’s belief in the power of decisionmaking

In the bitter cold January of 1988, a young woman expecting her second child faced the decision every mother hopes she will never have to make: between her own life, and the life of her baby.

Mary Beth Mathews was late in her second trimester when she found a sizeable lump in her breast. At first, she thought it was a blocked milk duct — but a visit to her local doctor revealed something far worse; she had an aggressive form of breast cancer. He advised her to begin chemotherapy immediately.

What will happen to the baby? Mary Beth asked. She was told she would have to leave it to fate. But in her heart, she knew the answer.

She returned to the dairy farm in Clymer, New York, where she lived with her husband, Ted, and their 2-year-old son, Casey. Paralyzed by the news, Mary Beth never really saw it as a choice, according to those who knew her best. She was due around the end of March or the beginning of April; she would not seek treatment until her baby was born. She would not risk chemotherapy harming or possibly killing the fetus.

“Mary Beth would have never, ever, ever ended that pregnancy. She would rather have given her life,” says Becky Faulkner, her sister-in-law.

At 32, Mary Beth Mathews was a beloved figure in the region. She was widely traveled, having taught English in Panama before returning to teach Spanish at a seminary in North East, Pennsylvania. But her true vocation was theater. A gifted actress, singer, and dancer, she was a star performer at the Erie Playhouse and other venues for years.

It was there that Ted Mathews first saw her, when his sister and her friend dragged him to see a production of “Brigadoon.”

Opposites attracted; the dairy farmer asked the actress to dinner, and sparks flew. Though she moved to the farm after they got married, she continued to act in the theater, even after Casey’s birth. One of her most memorable performances was the title role of “Evita.”

Ted and Mary Beth’s story could have been a plot line from a Frank Capra screenplay, until the day she was diagnosed.

One afternoon at lunch, Ted and Mary Beth had a visitor. Margaret Nyweide was well known around Clymer, having worked as a teacher when Ted was in school. (“If anyone had something worth listening to, it was her,” Ted recalls.)

Margaret had heard about their dilemma, and she wanted to help. She’d battled breast cancer herself, and she felt there was one place Mary Beth should go for answers: UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Ted and Mary Beth hemmed and hawed; they didn’t know what to think, or who would listen to them. But Margaret was insistent: “I’ll make the call for you,” she said.

She put them on the phone with her doctor, Scott Williams, who said he would gladly evaluate Mary Beth as soon as she could make the 2 1/2-hour drive to Pittsburgh.

Galvanized, they got in the car; and true to his word, Dr. Williams sat down with them at 8:00 that night.

“She wanted answers and needed answers,” said Dr. Williams, a cancer surgeon who frequently stayed late to sit with patients so he could give them more time to talk about their concerns.

Though he has since retired, he remembers the Mathews case.

“Young women — and she was one — they have a real concern. You want to try and understand as much as you can about a disease that’s impossible, on a single case, to understand.”

When Dr. Williams was in medical school, patients were never involved in discussions about their treatment.

“I was trained by guys who … did not tell patients they were going to have an amputation,” he says. “We didn’t tell them until the night before, because we didn’t want them worrying.”

Dr. Williams saw things differently. When he was training first-year students at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, he required them to interact with patients and learn how to involve them in decisionmaking.

“There’s nothing more striking than taking a first-year medical student, who’s in the first week of medical school, and you stand up in front of them and you have a 25-year-old breast cancer patient. You talk to her, and you talk to her husband, and all of a sudden, it hits home for these kids: ‘My God. This is what I signed up for.’ ”

Dr. Williams would ask the patient: What does it mean to be a good doctor? Describe for me a time when you thought a physician wasn’t interested in your welfare. As the patients answered, the room full of medical students was so silent, he could hear a pin drop.

In one case, a student addressed the young woman who was the patient.

“You know, this is my first week of medical school, and it’s very emotional,” he said. “I’ve got tears in my eyes. I’m going to have to do this a number of times in my life. Can you give me any direction?”

She looked him in the eye and said: “Be of (expletive) account.”

“That’s a great, great answer,” Williams says. “It puts things in perspective. If you’re not willing to be involved with patients, then don’t sign up for this.”

Because Mary Beth’s pregnancy was so far along, Dr. Williams offered her a new option: he would induce the birth in a month, then begin treatment.

“He was a super individual,” says Ted Mathews.

Their daughter was born on March 12, 1988; her parents were so grateful, they named her Molly Magee Mathews, to honor the care that saved her life.

“We were so impressed with the hospital and the people. So what else would you name her?” says Ted.

If you’re not willing to be involved with patients, then don’t sign up for this.

Dr. Scott Williams, breast cancer surgeon

For Mary Beth, there would be one more year. She drove back and forth to Pittsburgh for a long series of treatments. Family helped take care of the children and the farm; Mary Beth’s brother and his wife, Jon and Kathleen Finke, moved in temporarily so Ted could accompany her.

When the chemotherapy was over, Ted and Mary Beth traveled to Boston for a bone marrow transplant, which was experimental at the time. He iced her head to try and stop her hair from falling out. When she went bald anyway, Mary Beth put a headband with a bow on little Molly and a matching one on her own head and posed for a photo.

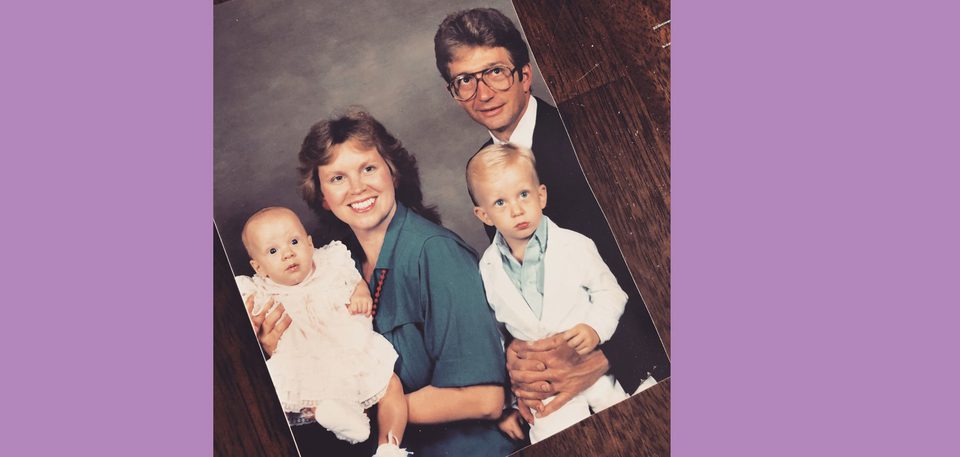

By the fall, she thought she was better. Her characteristically upbeat personality intact, she posed for a family photo with Ted and the children.

But by December, the cancer returned. A snowstorm hit the dairy farm, and Ted couldn’t find his wife; eventually, he located her walking around in a field.

“What are you doing?” he asked her.

“I don’t know,” she admitted.

It was the cancer, which had metastasized and clouded her ability to think clearly. Despite her illness, Mary Beth rallied enough to sing at a show, delivering for a final time the swan song of Evita Peron — a onetime actress who died from cervical cancer at 33.

The young parents spent Christmas in Pittsburgh; she underwent a mastectomy.

“After that, you were literally counting the minutes and hours watching the cancer move across her chest,” Ted said.

Shortly afterward, Becky Faulkner sat in her brother’s kitchen as Mary Beth said good-bye to her babies in the next room.

On her last trip to Pittsburgh, Mary Beth Mathews fell into a coma. Back home, 10-month-old Molly was hospitalized with pneumonia; she recovered, but her mother did not. Mary Beth died on Jan. 19, 1989, at 33.

“We were so impressed with the hospital and the people. So what else would you name her?”

Ted Mathews, whose daughter’s life was saved by the care at UPMC Magee-Womens Hospital

Molly Magee Mathews, now Molly Smith, never spent much time thinking about how she got her middle name when she was growing up; it was just an odd piece of family lore. She and Casey — an Air Force pilot stationed in Japan — were raised by their family on the dairy farm. Her father remarried when she was in kindergarten; on their wedding day, Molly asked if she could start calling her stepmother, Jackie, “Mom.”

Yet Mary Beth’s legacy to her daughter is apparent to those who knew her. Kathleen Finke sees it in Molly’s lighthearted personality, in her sense of humor, in her caring ways.

“Molly is such a blessing, and she does carry on Mary Beth’s memory,” says Kathleen. “She keeps it going. She’s just like her – she’s a good mom.”

Now 31, Molly is married and a mother of three children living in Nebraska, where she works with children who are transitioning out of foster care, helping them to develop independent living skills.

Because of her mother’s history, she underwent genetic testing; though negative for the BRCA gene, Molly remains vigilant.

“Since she was so young when she passed, I got my first baseline mammogram at 25, before we started to have kids,” she says. “I’m hoping it’s just a fluke thing and not my story, but I guess that’s to be determined.”

Be the First to Know

Get the latest research, news, events, and more delivered to your inbox.